Recent times have been extraordinary. The global pandemic has turned all our worlds upside down. The Government’s initial and urgent actions to lock the country down were necessary, and the response of the public has been nothing short of glorious. The virus has been contained, lives have been saved, and the immediate danger has been assuaged.

We now need to begin the long road towards rebuilding our lives and our livelihoods. Already we are being slowly introduced to the idea of a “new normal” with changes to the current strict regime, but after many weeks it will perhaps be more difficult to unravel the lockdown than it was to impose it in the first place. But we do need to adopt a middle way; the virus is here to stay until we find a cure and/or vaccine so we must find a way to live with it. For what is life but a series of gambles? We take risks every time we get out of bed (and sometimes when we get in!) We all learn to live with danger, to accept it where we must, and manage it down whenever and however we are able.

We are all, each and every one of us, accompanied by our own mortality and have been since the very day we were born. It never leaves us; it is always there. This pandemic, awful as it is, has merely highlighted this simple fact. I recall a strange 3-months period some 15 years ago when I was reminded of this, and when I became determined to enjoy my life to the full whilst I can, it is such a precious and fragile state.

Part 1 – Trains

On Thursday 7 July 2005 I had arranged to meet a prospective client in Richmond, Surrey at about 10am. I caught my usual commuting train from St Neots, a journey I’d done many hundreds of times before – there was a fast service that got into Kings Cross at about 8.30am, perfect for me to jump on the tube and get out to my rendezvous.

On arrival in London, on autopilot I walked across the Kings Cross concours and down into the Underground, and down again to catch the Piccadilly line train out towards Heathrow. The southbound platform was very busy, unusually so even for this time of the rush hour. A signalling fault had delayed a couple of trains, the crowd had backed up a bit – nothing alarming but it was difficult to move further down the platform, so I waited where I was and where the front of the train would halt.

Eventually a train came in. The doors opened, some people got off and then I moved forward with the crush to embark. My turn came, I must have been the last to get on. I’m a big chap and I usually get my way in a crowd. I squeezed into the rear of the first carriage, if I turned to face out and readied myself to duck my head as the doors closed then I should be OK but it was all a bit tight. I looked directly into the eyes of those who’d just failed to get on, shrugging at one chap and mouthing sorry, he ignored me as we do. The guy next to me clearly decided it was all too crowded, so he stepped off back into the waiting throng to wait for the next one. I chose to take my chance on this train, it was a close call but the next few would be just as packed. The doors slid shut, I and those around me relaxed into the space available and off we went.

“On arrival in London, on autopilot I walked across the Kings Cross concourse and down into the Underground”

It was unpleasant for a while, but the train slowly emptied as we left central London and I got a seat. I changed at Earls Court and arrived at Richmond at 9.30-ish, in plenty of time – I’m always early so that even when I’m late I’m still on time. I found a coffee shop. My prospect rang to say he’d been delayed, apparently there was some disruption on the trains, it looked as if he wouldn’t reach me anytime soon. I cursed him under my breath – I’d used that excuse before, if he hadn’t wanted to meet me he could’ve just said and saved me a wasted journey. Pessimistically I assumed he’d never had any intention of coming but I’d give him some grace and so settled back to complete my crossword.

Jo Wise and I are now married but in those days we just worked together. Love blossomed later. Jo is a Chartered Company Secretary and as such her main role was to manage all The Security Company’s business affairs whilst mine was to go forth and forage for work. We’d just moved into our new offices at The Barn. Back then TSC was still a tiny operation. In addition to Jo and I, the team comprised our book-keeper Avril, Tim the Techie and a couple of full time consultants. If we needed further help then we called in “associates”, freelancers themselves whom we engaged on projects as required.

“there was some disruption on the trains”

About 10-ish, Jo phoned me from the office. I was bored, I answered her call glad of the chance for a chat. “Oh, thank God. Where are you?”, she asked without any preamble. I could sense the fear and urgency in her voice so assumed there was something wrong at home or with my kids. “Richmond. Where I’m supposed to be. Why?” “Are you alright?” “Yes, why, what’s up?” “They’ve bombed London. The Underground. Are you sure you’re safe?”

I’d no idea what she was on about. Slowly, together, over the next hour or so, me in a coffee bar in Richmond, she in Cambridgeshire, we unpicked the situation. She watched the news on tv and translated events to me as they unfolded. A small group gathered round my table in the cafe, in turn I translated to them.

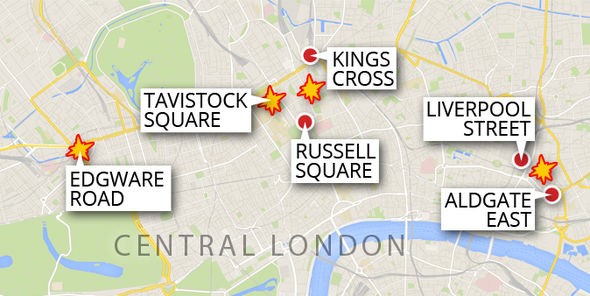

London was now closed. The police had it in lock down. There had been a series of coordinated terrorist bombings that targeted rush-hour commuters on London transport, an attack that was to become known as “7/7”. More than 50 people had been killed and more than 700 injured. Many commuters had been trapped underground.

Four bombs had gone off altogether, three within seconds of each other at 8.49am on separate underground trains, and one an hour or so later on the top deck of a bus at Russell Square. The four suicide bombers – so-called “cleanskins” in that they were previously unknown to the authorities – had travelled together from Luton by train, arriving at Kings Cross at about 8.30am and dispersing from there on their separate lethal missions. They each had carried their deadly cargoes in rucksacks slung on their backs, they had all died in the attacks.

Eventually I grabbed a taxi and made my way to Heathrow airport – by now no trains or buses were running at all. Jo drove down from Cambridgeshire to pick me up. We travelled back in silence along a deserted M25, listening to updates on the news.

I’ve reconstructed those fateful minutes many times in my mind. I have no doubt that the Piccadilly Line bomb went off in the train that immediately followed mine. The bomb went off in the first carriage, the same carriage that I’d boarded on the train in front of it. Exactly half of those killed that day (26) died in that carriage, the explosion having occurred some 500m into the deep, narrow tunnel from the Kings Cross platform.

The bomber must have been in the crowd just behind me. He must have boarded through the same set of double doors. Those killed must have included those on the platform behind me and whose gaze I’d met as I’d waited for the doors to shut. Perhaps the casualties included the chap who’d decided to step off and wait for the next train, as I’d been tempted to do.

There had been considerable confusion in the immediate aftermath of the explosions. First reports were of a power surge, it wasn’t until mid-morning that it was officially confirmed the incidents were terrorist attacks. My train must have moved just ahead of the wave of destruction and disruption, its driver ignorant of and unaffected by the carnage unfolding behind.

I could have been in that carriage, but I lived to fight another day. I never followed up with the prospective client.

Part 2 – Planes

For nearly forty years my old dad had been a schoolmaster. Not a teacher, he would say, a schoolmaster, the difference to him was important. He would often be called upon to teach subjects outside his mathematics specialism, as was the way back in the day if a colleague called in sick. I would love to have seen him try to teach French! I do remember him once saying “You just have to keep 20 minutes ahead of the kids and no one will realise how little you know”.

It was very early in the Noughties that I started working with a training company, Ifex. I can’t recall now exactly how we’d met, but I was still broke from my losses to a con man and so grabbed at the chance to run a couple of short courses for them in London on the principles of financial fraud (a topic I was at the time entirely unfamiliar with but I managed to keep 20 minutes ahead). The deal was that I would run the courses for expenses and a very small fee but any follow-up consulting work that I won was mine. Needless to say, no follow-up work ensued but it was all good experience and I learned a lot.

Then suddenly I found myself boarding a very dilapidated British West Indian Airways (“Bee Wee”) Lockheed Tristar en route to Trinidad, to run a major 4-day course for Ifex on the basics of computer security in the financial services sector. My audience would be senior executives from a number of Caribbean banks, Ifex had billed me as a “leading expert in this emerging field”, and I just prayed I had enough in the hopper to maintain the magical 20 minutes lead over my students.

“Suddenly I found myself boarding a very dilapidated British West Indian Airways (“Bee Wee”) Lockheed Tristar en route to Trinidad”

Actually, it all went rather well. Wisely as it turned out, I’d invited along an old chum Rod Parkin (recently retired ex-Midland Bank and an experienced computer auditor) to share the load; he’d agreed to come just for the ride and the experience, good news since I had no budget to pay him. The course was held at the splendid Hilton Hotel, Port of Spain and both of us were bowled over by the Tropics. Neither of us had ever experienced the likes and we had huge fun. Our class were delightful and engaged, and Rod and I and a top lawyer also flown out from London made a pretty good fist of the teaching. No one noticed how little we instructors knew – thanks again, Dad, for the advice. At the end we managed to negotiate a couple of extra days by the hotel pool, enjoyed the exotic nightlife in the bars listening to the steel bands, and generally made the most of an unexpected bonus in the sunshine before flying back to the gloom of the UK.

On this occasion I did get a follow-up assignment, from the Republic Bank there, and went back to spend many happy months on assignment as Head of Security – but that’s another tale for another day.

Over the following few years, I ran other courses for Ifex in Trinidad but also in Europe, the Middle East and across Africa. I formed a regular academy of speakers and we travelled together to these far-flung places. I grew fond of Ifex’s Managing Director Albert Adomakoh, a delightful Ghanaian from a high-born family whose father had been the Governor of the Bank of Ghana in the 1960s. Albert had been sent to England as a young boy of three to a pre-prep school in the same tiny village as I then lived – we were both blown away by this coincidence. He’d attended Dean Grange School in Cambridgeshire as a boarder pretty much full time until his early teens, returning only occasionally to his homeland for rare holidays with his family. Although the school had long closed I knew the family who’d subsequently bought the big, old house and its outbuildings, and arranged for Albert to visit for a look-around. He found it a very moving experience.

“I grew fond of Ifex’s Managing Director Albert Adomakoh, a delightful Ghanaian from a high-born family”

Albert had gone on from Dean Grange to Charterhouse School and then Oxford University. He was tall, handsome and charming. An imposing but gentle giant of a man and a committed Christian, he was always impeccably dressed, with the best of manners and the thickest Queen’s English cut glass accent I’ve ever heard before or since. He was always very straight in his dealings with me, so when in October 2005 he called about the new West African Financial Crime Prevention Course he was developing and wanted me to run in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, I felt rather bad in declining this and any future opportunities. By then I was back on my feet financially, I had become tired of the frequent travel to hot and strange lands, and I had huge plans for the fledgling SASIG that was demanding my attention. In addition, my father had recently died and at least in the short term I needed to be with my mother who lived nearby.

The course was to be organised in conjunction with the Nigerian National Drug Law Enforcement Agency and the West Africa Bankers Association, so it was a big deal. Albert offered me increasingly large sums to take the assignment, but I stuck to my guns and in the end he conceded gracefully. We promised to stay friends and keep in touch. I knew the others had agreed to join him as usual and I wished them luck.

“I had become tired of the frequent travel to hot and strange lands, and I had huge plans for the fledgling SASIG”

Albert invited Martin Grieves to take my place as course leader for this and future events; I’d never met Martin but knew of him as a hugely experienced fraud investigator who’d served with distinction for many years with the Metropolitan Police and then at the Serious Fraud Office and Citibank before (just) starting his own consultancy. It seemed a perfect fit.

The whole team of instructors were slated to fly out of London on 22 October 2005, first to Amsterdam then to Lagos and finally to Abuja. With hindsight it seemed an over-complicated journey involving several changes and a mix of airlines. Our young American cybersecurity expert based in Brussels opted to pay the difference to fly direct from Amsterdam. Our top London lawyer couldn’t get away straight way so planned to travel down the next day. The two London-based course administrators had been sent a couple of days ahead to check that the hotel and venue were all in order.

So, in the end only Albert and Martin left as originally planned. By the evening they’d reached Lagos and transferred to Bellview Airlines Flight 210 for the final leg to Abuja. The Boeing 737 aircraft crashed shortly after taking off, killing all 117 people on board including Albert, Martin and two Nigerian delegates attending the course.

A Bellview Airlines Boeing 737-200 similar to the aircraft involved in the accident

The cause of the crash has never been determined. Neither of the black boxes were recovered. There was speculation at the time that the flight had been sabotaged but no evidence of this ever emerged; true, there had been many senior Nigerian government and law-enforcement officials on the flight, but the subsequent crash investigation revealed such a catalogue of other more obvious factors that I’ve never believed mischief to have been the cause. The report highlighted that the captain hadn’t been adequately trained and had been over his hours in the days before the accident; the airline had failed to follow operating and maintenance regulations; and the aircraft was carrying a number of technical defects such that it shouldn’t have flown then or on several earlier flights.

I should have been in that airplane, but I lived to fight another day. I’ve never been back to Africa since.

Part 3 – Automobiles

It was the Sunday after the Nigerian air crash. My dear old mum was still with us in those days, my father had died earlier that summer and I was being very conscientious in my caring for her. She was putting on a brave face, but she missed him terribly after 61 years of married life with him and things were still all very strange to her. I was on my own, so it was no great hardship to me to spend time with her. In fact, I discovered her to be a fascinating, funny woman and great company.

She’d spent the day with me in my house in Kimbolton, I’d cooked us a late lunch and we’d enjoyed watching Songs of Praise together before I took her home. I’d taken to using my dad’s old Ford Fiesta. He always had terrible taste in cars and this one was no different, but Mum liked me to drive her in it. She lived in St Neots, about fifteen minutes away, I’d done the journey a thousand times or more before.

Between my home and St Neots, on a very fast stretch in the open countryside, there is a set of switchback curves that catch out many motorists unfamiliar with the road. Indeed, one of my eldest daughter’s friends had been killed there only the year before, after crashing head on into an oncoming vehicle, so as ever I was cautious and alert on my approach to the curves.

“On a very fast stretch in the open countryside, there is a set of switchback curves that catch out many motorists unfamiliar with the road.”

It was dark but dry. Several sets of headlights were coming towards me, suddenly something didn’t seem quite right and instinctively I slowed almost to a halt. Headlights went past us as normal on the right, but another set of headlights went past us on our nearside as well, as one of the oncoming cars veered violently and at high speed across our bows and bucked out of control along the grass verge on our left. We were showered with grass and mud. I could hear the scraping and banging as it passed us by. It came to rest on its side in the ditch, one headlight shining across the fields whilst the other pointed into the air, and its wheels spinning slowly to a halt.

Other oncoming cars and cars behind us had stopped by now as well, their flashers on, people getting out in the dark. Mum and I just sat there transfixed. Someone knocked on my window to ask if we were alright. The police arrived, the road was closed, the young lads in the crashed car seemed unharmed and were breathalysed, and we were asked to drive on. “Nothing to see here, sir”, said the very young cop, as if I’d just stopped as a rubbernecker. I moved off. Neither of us had said a word so far.

“That was close”, said Mum quietly as we arrived back at her house. I saw her into her apartment and then left. By the time I passed the scene a breakdown truck had arrived.

Mum and I never spoke of the incident again. If our timings had been different by even a second, we would have both died in that cheap, little car on a dark, Fenland road in the middle of nowhere.

But I lived to fight another day. Mum lasted another happy decade.

Postscript

In 2012 Jo and I married and moved into Dean Grange, Albert’s old school. Our rich farmer friends had renovated and converted it into a luxury house for themselves but then they’d moved on to an even grander place. We rented it from them as a stop gap home, intending to be there for no more than six months whilst we reordered our new life together. In the end we stayed there for six years and loved it.

Dean Grange – once a school and our happy home for 6 years

There were many times when I imagined a young Albert running down the hallway, or up the stairs. Our lounge was the old dining hall. His old dormitory was my home office. Our bedroom had been the Headmaster’s office, our dining room a classroom, our kitchen the sanitorium. Occasionally we’d get past pupils stopping by on trips down their memory lanes, wanting to look around, we always let them, generally they had happy memories of the place.

One of them remembered Albert. I remember him every time I fly.

And so, to today…

In 2005, in the space of three short months, on three occasions whilst going about my normal business and doing nothing unusually reckless or dangerous, I had come close to a certain and violent death. Each time, with no input from me what-so-bloody-ever, fate had aimed and missed. The world has pretty much left me alone ever since. Already, I’ve had an extra fifteen years. I’m still here, folks, and counting.

To comment on this blog, visit Martin’s LinkedIn article here…

Read more of Martin's Log

Thank you for reading my blogs. I’m getting quite old now, and hopefully I’m a little wiser than I once was. I have enjoyed a fascinating career full of fascinating people, and made many great friendships. I’ve made huge errors in my lifetime, and enjoyed great success too – it’s been the ultimate game of snakes and ladders - up and down, round and round. It is my privilege to share some of my stories with you, and describe some of the lessons I’ve learned in the hope that it may both save you from falling into the same holes, and help you in your careers and lives. Good luck and good fortune.

More blogs